You are in preview mode

Tissue engineering: how it allows us to build organs in the laboratory

Tissue engineering has the huge potential to resolve specific medical needs, like creating organs for transplantation. But how can we create organs in the laboratory? This article offers a brief exploration of how we can combine cells, materials and exciting technologies in the development of artificial human tissues. |

Why is the scientific community interested in building organs in the laboratory?

There are currently thousands and thousands of people in the world waiting for an organ transplant for critical organs like kidneys, heart and liver that could save their lives. Unfortunately, there are not enough organ donors available to fill that demand. What if we could create new, customized organs from scratch? Building organs in the lab could save millions of lives.

Tissue engineering is a relatively novel field in which biologists, doctors, and engineers work together to assemble organs which can be transplanted into patients, reducing the number of people dying while waiting for a transplant.

The first definition of tissue engineering was given by Langer and Vacanti in 1993 who defined it as ‘an interdisciplinary field’ that uses principles of engineering and biology to develop biological ‘substitutes’ that improve or replace tissues or organs. The concept is very promising and constant advancements in the field show that the goal could be achievable. But what is needed to build an organ from scratch? There are three main components that scientists are trying to assemble to create working tissue that could be transplanted into patients.

1. The right scaffolding.

The first thing we need to do to build an organ is to study and re-create its 3D structure, the backbone, which we call “the scaffold”. There are different approaches to do so.

Some research groups are working using bio-ink and 3D printing technology. For years, scientists have predicted that 3D printing – which is now used to make several objects like toys, tools, dental implants, prosthetics and even houses – could be used to print live, human body parts. However, printing live cells that support the function of a living organ, is much more delicate and complicated than printing with plastics and metals. So scientists are now working on the best way to achieve this.

No research group has yet been able to print fully functional, transplantable human organs, but scientists are getting closer. In fact, scientists have printed mini versions of organs using specific microfluidic devices, also known as “organs on chips”. Organs on a chip have increased knowledge of the function of the human body. Some of these models are also used by pharmaceutical companies to test drugs before moving on to animal studies and eventually clinical trials. But 3D printing is not the only possibility we have to produce human organs in the laboratory.

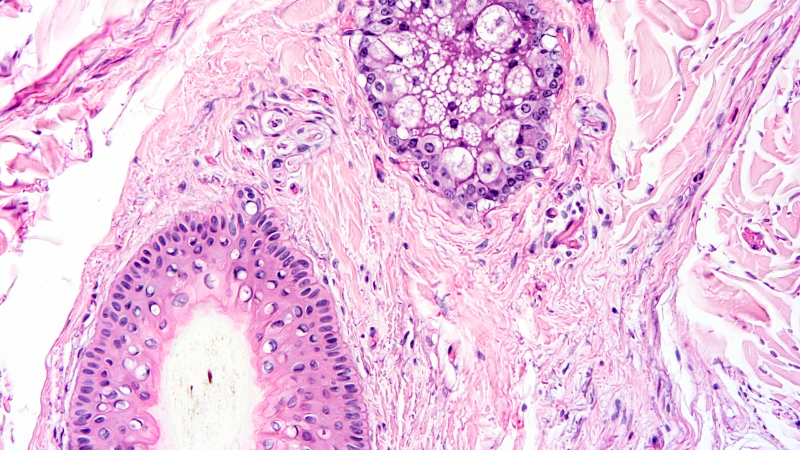

Scientists have found a way to rebuild organs in the laboratory starting from the backbone of the organ itself. However, to do so, researchers had to find a way to remove all the blood and cells that the organ was made of. This process is called “decellularization”. The process is very visual: the organ, usually a pink/reddish colour and dense, gradually becomes white and translucent. What is left, is the natural skeleton of the organ, a mesh of protein of the Extracellular Matrix (also called ECM). By decellularizing organs, the scientists have obtained 3D scaffolds which have the shape, the structure, and the same components as the organ of origin. This has many advantages because cells seeded (injected or placed inside the scaffold) will find an environment, composed by the ECM, which really resemble the tissues of origin. This helps the cells to get well acquainted, to “get cosy” and to perform the function they have in the organ.

2. The right cells.

Every organ of our body has different types of cells that are responsible for that organ’s specific function. For example, mature tissues like skin, muscle, blood, bone, liver and nerves, all have different types of cells. It is then obvious that artificial organs made in the laboratory will need to contain the same specified cell types present in the original organ. However, in most cases, it is very difficult to obtain and grow cells from human organs in the lab. A possible solution to this issue is offered by stem cells.

Stem cells are undifferentiated cells (they do not, yet, have any specific function or belong to a specific organ) which have the unique potential to produce any kind of cell in the body and can self-renew (which means copying themselves several times). When an organism grows, stem cells specialise, or differentiate, and take specific functions and therefore they can become specialized cells. Organisms also use stem cells to replace damaged cells. Stem cells can be cultured in the lab (culturing cells is also called tissue culture and they can be transformed into specialised cells).

For reconstructing an organ in a lab, using a tissue engineering approach, stem cells can be cultured in high numbers (because of their self-renewal skill they can become very many). Then differentiated into the specialised cell type of the organ and seeded (or injected) into the artificial organ (produced via decellularization or 3D printing).

3. The right biomolecules.

An organ in the human body constantly receives nutrients, oxygen, and molecules through the blood. As you can imagine it can be very difficult to recreate this “in a dish” in the laboratory. It represents a crucial step to work on to translate tissue-engineered organs to the clinic. Nutrients and molecules that cells in artificial organs need can be supplied in the culture medium (the sugary pink/red solution cells are grown in). But dipping the artificial organ in the culture medium in a tissue culture plate is not enough for the organ to survive and for the cells in it to receive all the stimuli they need to perform their function well.

To create an environment that is richer than a simple laboratory plate, many scientists and engineers are working side by side to develop bioreactors which allow the culture of artificial organs for long period of time. Bioreactors can have different shapes, to accommodate the shape and size of the organ, and can be made of different materials. Some more advanced bioreactors can be connected to little computers recording the pH, oxygen and nutrients levels in the medium in which the organ is cultured.

The tissue engineering field is moving fast to develop techniques that will produce organs in the laboratory. This field is very interdisciplinary: biologists, engineers, doctors, and surgeons work together to bring these organs from the lab to the hospitals. So, if you have an interest in this topic you can contribute from a medical, a biological or engineer perspective, depending on what you like the most! And by doing so you could help save many lives!

Additional information

Do you like this topic? Have a look at these resources:

YouTube, TED Talk by Anthony Atala: “Growing new organs”

YouTube, TED ED “How to 3D print human tissue” – Taneka Jones

Stem Cell @Lunch Digested. https://soundcloud.com/user-563815853 King’s College London Centre for Stem Cells & Regenerative Medicine

EuroStemCell – a website full or resources to find out about stem cells and stem cell research

Liver Engineering and Regeneration group. Institute of Hepatology, foundation for liver research.

Glossary

Tissue engineering – discipline that combines cells, engineering strategies, materials, and factors to restore or replace human organs.

Bioink – A Bioink is the material used to produce engineered (artificial) live tissue using 3D printing technology. Bioinks are usually in form of gels and contain different molecules, protein and sometimes cells too.

Organoid – tiny, self-organised 3D tissue cultures derived from stem cells.

Organ on a chip – Organ-on-chip are devices, mostly no bigger than a LEGO®-brick. Organ-on-chip are made from polymers (huge molecules that are long chains containing many of the same small molecule, plastic is an example of a polymer). They contain many small channels and chambers in which liquids or gases flow through. The chambers provide a cosy environment for the cells, which helps them to forget that they are not in the body anymore. The cells can arrange themselves similarly to the way they would in the human body, forming mini-organs.

Decellurisation – the process to chemically or physically remove the cellular compartment of living tissues, creating an acellular ECM scaffold that can be used for various purposes

Extracellular Matrix (ECM) – the extracellular matrix (ECM) is a three-dimensional network consisting of proteins and macromolecules and minerals (such as collagen for example) that provide structural and chemical support to surrounding cells. The ECM is the non-cellular component present in all organs.

Tissue culture – Tissue culture (or cell culture) is a way to grow cells in a laboratory. Cells are taken, and put into in a flask or Petri dish and cultured on a growth medium. The cells divide, and can be treated in various ways. This is done for a number of purposes, especially for the use of scientific research.

Bioreactor – any manufactured device or system that supports a biologically active environment under controlled conditions. In tissue engineering, a bioreactor is necessary for the in vitro development of new tissue by providing biochemical and physical signals to cells.

Self-renewal capacity (of stem cells) – stem cells are able to copy themselves and generate more stem cells.

Types of stem cells – the two broad types of mammalian stem cells are: embryonic stem cells, found in the embryo, and adult stem cells, which are found in adult tissues. In a developing embryo, stem cells can differentiate into all of the specialised embryonic tissues and then give rise to all different cells in our body. In adult organisms, a group of adult stem cell is present in specific organs and act as a repair system for that organ, replenishing specialized cells, but also maintain the normal turnover of blood, skin, intestinal tissues, and others.

Find out more

Langer, R & Vacanti JP, Tissue Engineering, Science 260(5110), 920-6, 1993

https://www.the-scientist.com/news-opinion/on-the-road-to-3-d-printed-organs-67187